An educator, researcher and podcaster, he gives an insight into how his online method unfolded amid the pandemic.

The technicality of it

Before the announcement came to revert to online-only teaching, my home was already set up for it. I had been using zoom from well before the pandemic. I happen to do podcasting on a regular basis, so I had lamps, a Bluetooth speaker and an HD camera with an integrated microphone. That’s all you need, really. No need for expensive TV-level equipment or a soundproof broadcasting studio.

I also happened to have a beamer and a projection screen at home, so I used those as well. The trick is to place the camera between where you’re standing and the wall you’re projecting on, so you see your students’ faces on the zoom wall, while the students see you as if you were looking directly at them in the actual auditorium or classroom. As simple as that. For them, and for me, it was an online interaction with a genuine ‘real-feel’ feel. The rest is just lecturers’ craft and charm.

Since students often remark on how I move my hands a lot when I talk, and that this helps them to follow what I’m saying more easily, I didn’t want to sit behind a desk or have messy cabling causing any distractions. The ethernet connection was the only cable I needed for broadcasting quality. My set-up allowed me to move around freely and move my hands as usual.

By sheer coincidence I’d opened a WhatsApp business account to coordinate appointments with research interviewees. Since I knew this year was going to be emotionally charged, I used the same account to set up a group for my students in case they needed instant advice or a listening ear. I wanted the students to learn something relevant and feel connected with one another, but at the same time stay as sane as possible.

Online teaching as art and science

I continued to use the syllabus from previous years, but had to rethink how to adapt it to an online format. I couldn’t expect students to pay attention to me on a screen for two hours if everything was read out while they were for instance lying on the sofa, staring at the sky. Instead, I did online ‘briefings’ with them where I focussed on the essential bits followed by a Q&A, rather than online lectures.

I teach health sociology, and decided to approach teaching in a problem-based learning way. It invites students to work on real-life cases that they could easily encounter outside university such as medicalisation of eating or using ‘health’ as a branding strategy. It allows them to go from an observational level to the theoretical, which makes life easier. From there, they identify what they know about the particular case of the week, what they don’t know but would like to learn, and what resources they need to achieve their learning goals.

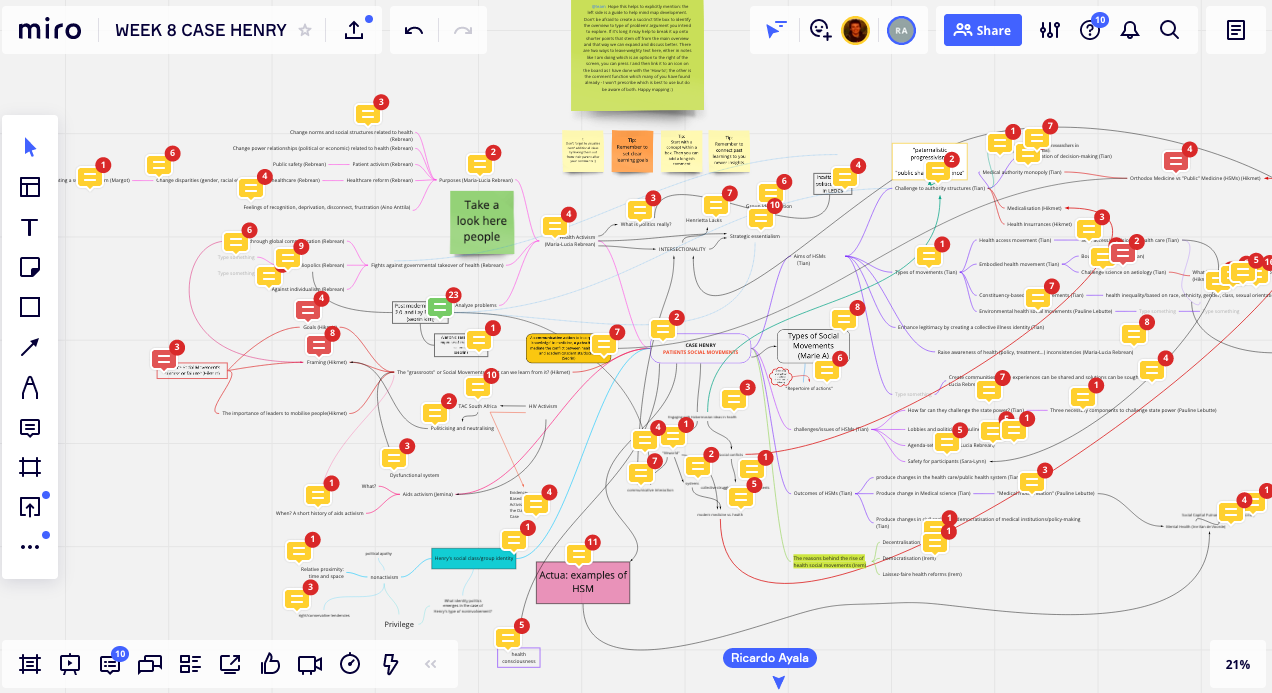

Sharing information is key, as is the exchange of perspectives, as it helps maintain a distance from the idea of individual success, which I find pernicious. Collaborative note-taking on an online platform was done throughout the week, where I gave feedback and encouraged further discussion, but the students did all the work in a non-linear fashion, like assembling a large jigsaw together. With some practice, students’ questions became more complex, going from ‘what’ to ‘how’ to ‘what if’-questions, showing how they acquired a better understanding of the subject. The online platforms proved to be great for those who don’t like speaking in public. Here is an example of the comments board we created to gather up questions [continue reading below picture]

Knowing that this generation is much more visual than my own, I introduced a knowledge clip as a substitute for the mid-term paper. I’d written in the past about the dominance of text in academic culture, so I thought to extend this to teaching. The point of the knowledge clip is for students to illustrate a case of their own and frame it theoretically. It does not involve any technical dexterity for animation or videoing, but requires quite a few hours of studying, scripting and practicing because they need to reduce the complexity of the theory. Simplifying concepts is harder than it sounds, especially if the video is to be maximum 2 minutes.

Back then I was home alone, but for once the grading didn’t feel like that lonely thing you do behind a desk. Wrapped in a cosy blanket on the sofa while sipping hot chocolate, it was like watching a playlist on YouTube. The students’ videos reflected exactly what visual scholars do: combining imagination and rigour. The grades tended to be higher when the assessment was more playful, which isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, but it gave students a reason to go ‘the extra mile’.

What could not be done

The planned excursion around Christmas time didn’t go ahead as planned, but we managed an online tour of a World Health Organisation facility in Trieste (Italy), so students could see theory being applied and ‘translated’ into social integration programmes.

Funnily enough, to date, I’ve not met my students in person. I’d have loved for them to come to my garden, by the campfire, in smaller groups, to discuss their ideas in person, but every time that seemed possible, there were new measures. Maybe during the next pandemic.

Students’ appreciation

The results of the evaluation survey of VUB courses were recently known. As every year, students were asked to assess each course along different parameters, such as study goals, contents of the course, accompaniment, study material and evaluation. In international programmes, such as this one, students were also asked to assess foreign lecturers. While online teaching is not always a satisfying experience, VUB health sociology students thought online classes were high quality, lively and enjoyable.

There’s something immensely rewarding in hearing your students appreciate your work. For me, the course evaluation survey was both a pleasant surprise and a true lockdown life-enhancer. I don’t like putting myself on a ranking of any sort, like a ‘success’ ladder – I don’t like going around comparing myself to others. One thing is for sure: I don’t believe you can ever really teach, unless you love learning.

I feel grateful for the students’ presence in my home every week, just as they let me in their private space. It was an escape from the daily news. If I could do it all over again, I would.

>> want to have a look at one of the knowledge clips? Here is one to check out.

>> Ricardo is a social scientist who holds a master’s degree in education specialising in adult education, tutoring and lifelong learning. He joined Ghent University as a doctoral researcher in 2010 and teaches at VUB since 2018.